I recently read the cover article in the April issue of Vanity Fair about Gisele Bündchen. I’ve never thought one way or another about Gisele— she’s so obviously beautiful in the same way that undeniably arresting and genetically freakish products of nature often are. (I put snow leopards, blue morpho butterflies, and albino snakes in this category as well.) Still I was curious to read the article mainly because my sister characterized her as a “white witch” (Gisele self-identifies as a “witch of love”), and that piqued my interest enough to tear me away from the reels of rescue/makeover stories of stray cats and kittens I’ve been spending hours of this one wild and precious life consuming with seemingly endless patience and ruthless abandon.

It turns out that Gisele is spending her days post Tom Brady in an eco wonderland of her own design, living life barefoot and surrounded by crystals in the forests of Costa Rica; communing with small animals, raising chickens, riding horses on the beach and teaching her two children to trust their intuition™. She comes off as perfectly nice, fairly grounded and almost completely without edges. I almost couldn’t muster the energy to finish the short piece, reading it felt a little like taking a rest under a cashmere throw on a linen ecru couch— inviting in a way that soothes as much as it unsettles (who lives like this?).

More and more I find myself perplexed by the space we give to these stories; of people ensconced in beauty, fame and wealth (or any combination of the three), who come off as so walled in by their own experience —by privilege, luck, or circumstance of birth—that they appear to the outsider as ultimately just really, really boring. I assume it’s the competing need to self-promote and self-protect that robs them of their juice, a professional smoothing over of the rawness and the messy that, if they were able/willing to divulge, would make them actually relatable and fascinating in spite of the pedestal we’ve placed them on.

But perhaps that blandness is what we need from her. Adoration of Gisele’s physicality is the point: her nickname is literally “the body.” She is supposed to be our our icon of the unattainable aesthetic ideal. If we are to continue to draw from the well of her beauty, she cannot be too real, or everything will be spoiled. She must maintain an image of perfection: a model immigrant (yes, double meaning intended), and an angel among us (again, intended), devoted to tending to her children, small creatures, quarterbacks and the earth, all the while ageless, dolphin-smooth and wrinkle-free in a lamé crotch flossing swimsuit.

Gisele, bless her heart, is not of use to me at this stage in my life. Not even her beauty penetrates. I want to see her 3-inch-long chin hairs, the ones that somehow seemingly sprouted overnight (WTF are these anyway???) and evaded all detection until she was sitting in juuuuust the right lighting. I want to know how she really feels about being the subject of the world’s gaze, and whether or not she is tired of the role. More importantly, I want to hear other stories— stories that tell the truth.

Pondering Gisele as the world’s muse reminded me of an experience I had standing underneath Rodin’s sculpture The Burghers of Calais in Ca’ Pesaro here in Venice. I’d previously seen bronze versions of the same sculpture at the Cantor Museum at Stanford University and at the Met in NYC and walked by without feeling much of anything; Rodin’s never really done it for me. This time, however, was different. I stood there, mouth agape, moved deeply by the piece. I could not tear myself away.

I was alone in the room, so I took the opportunity to slowly circle the figures, trying to understand what is was about them that I was finding so compelling. Was it the material—plaster instead of bronze—that changed the visual impact? Or was it simply my age, older now and tired in the same ways these men look tired, the lighting, or the way they were oriented in the space? My gaze kept being drawn back to the sinewy tendons and knobby joints of the hands and feet— each of the figures expressing a lifetime of struggle and also a quiet gracefulness that I hadn’t previously noticed. That was it. It was the hands and feet, they were the magic.

On the boat ride home I dove into the history of the sculpture, and lo and behold, a predicable tale emerged. It turns out that many art historians believe that the artist Camille Claudel was in fact responsible for sculpting the hands and feet.

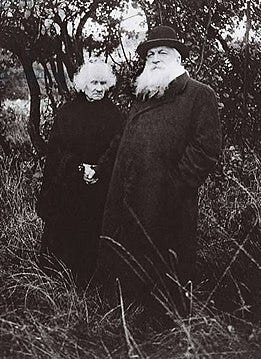

The story of the relationship between Camille Claudel and Auguste Rodin is usually told with Rodin positioned as the older more established and successful artist, and Claudel as the student and muse— brilliant and successful for her time, despite being tragically female. Their romantic and artistic relationship lasted for over 10 years, with his career ascendant and hers eventually floundering as she descended into “madness” and institutionalization.

But of course, the real story is far more nuanced and layered. Although Rodin started as Claudel’s teacher, their relationship shifted over the years to become one of mutual inspiration and collaboration. According to Jules Desbois, a fellow sculptor in Rodin’s workshop, for over a decade Claudel was instrumental to Rodin’s creative process. He looked to her for guidance and opinions, drawing inspiration from the work she was making and enlisting her help as both a model and fellow artist. Rodin also claimed ownership of at least two of her sculptures, including The Slave and Laughing Man, which were modeled in clay by Claudel but eventually cast in bronze and signed by him.

The thing is, Rodin already had a domestic partner: Rose Beuret. She was the one who cooked his meals, bore his child, and stood by him throughout the vicissitudes of his career. She managed the domestic sphere of his life, while Claudel fed his intellectual and artistic needs. Rodin routinely promised Claudel that he would leave Beuret but never followed through. Not surprisingly, Rodin’s unwillingness to commit pushed Claudel over the edge.

After an abortion in 1892, their romantic relationship ended, leaving Claudel adrift. Without close proximity to Rodin’s clout and influence in the art world, Claudel began a long process of unravelling. Though Rodin attempted to help her obtain commissions, she became increasingly convinced (many texts refer to this period as “paranoia”) that contact with him would result in the theft of her ideas. Her brother and mother refused to support her financially after her father died, and the high price of bronze casting made it nearly impossible for her to complete works independently. Although she was able to make some of her best work during this time, she also destroyed many of her sculptures. In 1913 her brother forcibly committed her to an insane asylum where she spent the next 30 years —the remainder of her life—and never worked again.

Claudel’s story is often told as a descent into madness, of a woman in love and then scorned; consumed by envy, romantic betrayal and ultimately self-destruction. Viewed from the perspective of middle age in 2023, I can imagine another possible version. Claudel, a talented, driven, visionary artist had few opportunities to make the art she wanted to make. When she met Rodin she saw a creative partner, and maybe an artistic equal. Their love was built on mutual attraction, both creative and sexual. And yet, due to the intractable constraints placed on her by French society, her family and the art world at the time, she was unable to realize her potential. The relationship she built with Rodin mutated from symbiotic to parasitic. He not only coopted her work, and her ideas, but refused to marry her, sucking her dry of everything she could give him. He took everything. She was left penniless, isolated and heartbroken, her mental health in tatters, never to make her art again.

Who would Rodin have been without those two women, Camille and Rose? His story of individual genius is completely blown apart by the presence of the two people working tirelessly behind the scenes (yes, working) to make his life easier and more fulfilling. They were his collaborators, along with the dozens of other people who apprenticed in his studio and worked for him at his home.

The role of the muse, the framing of who and how one becomes one, has long been a subject of fascination for me. The gendered positioning of the woman who inspires men (it’s almost always men) by virtue of her beauty, a connection to the divine, or simply because she is the physical embodiment of a portal to creative inspiration, is the background narrative of so many stories of “genius.” She’s the behind the scenes sparkle, the enchanter, the og manic pixie dream girl. Her role is also passive. She is there to be consumed by the genius, who processes her gifts through the expression of his talent: creating his great art, music, poetry, scientific discoveries, etc.

The trope of the muse is also so fucking tired. It ignores the complex ecosystem of each of our lives, and how each person we engage with relationally plays a unique role in shaping who and what we become. Rose Beuret wasn’t any less an influence on Rodin because she cooked the meals, washed the dishes and changed the diapers —she managed his life so that he could have the time and the space to create, carry on passionate affairs and devote himself to the Parisian art scene. Who knows what her own aspirations, creative ambitions or intelligence were.

When I first met Andy he was paying his way through college making Tiffany glass reproduction work. I was in awe of his technical skill and dedication to learning his craft. I lived in San Francisco and he lived in San Luis Obispo, so I decided that the best way to seduce him was with intaglio prints, collages, photographs, mixed tapes, bad poetry and long meandering letters that I sent to him in the mail. He replied to these overly enthusiastic products of my infatuation with beautiful collages and spare notes. That back and forth was the beginning of a creative conversation and partnership that has continued to this day.

From the beginning he was the specialist and I was the generalist. He focused and I dabbled. I hadn’t narrowed in on a singular artistic path, and I had no desire to sell what I was making (still don’t), so we established our roles based on the circumstances we found ourselves in at 22 and 23-years-old. I would be the stable income, and he would continue to build a career making glass. This de-facto structure led me to earning a master’s degree in teaching visual art, landing a solid job, and digging into my role as an art teacher. I never stopped making things, but I did it haphazardly. My studio was the kitchen table and a few shelves in the storage room at my school. I made things when I had the perfect synthesis of space and time, which over the years became harder to achieve.

At work I devoted myself to designing studios and curriculum meant to foster other peoples’ creativity. Each work day was a marathon of brainstorming, coaching and artistic guidance. I’d rattle off lists of ideas, show videos, pull books, send links, make sketches, help with free writes and talk and talk and talk. I’d give working feedback, critiques, reviews and edits. I’d listen, suggest and mull over, providing as much or as little support as each person needed. Then, I’d go home and do the same for my partner.

For many years it felt like enough. I didn’t really mind that the conversations and ideas and thought experiments came to life through the hands and labors of others. I was proud to be a part of it all, satisfied enough that some spark in my person lit fires for others. I celebrated when they made the thing, or realized the vision, knowing that I’d played a small but crucial role in the genesis.

And then I had Cleo. After she was born I didn’t paint, work with clay or write for over three years. During that fallow period I told myself that my creative expression was raising a human and gardening. I was sleep-deprived and hustling so hard that the idea of making space for art felt utterly impossible. I buried my creative ambitions so deeply that I stopped believing they had ever existed in the first place.

When Cleo was one Andy won a prestigious award through the Smithsonian Museum. The three of us traveled to Washington D.C. to attend the awards ceremony and see his work installed in the Renwick Gallery. It was a huge milestone in his career, and I was incredibly proud of him. I was also exhausted, suffering from postpartum depression and trying to manage a toddler who was just learning how to walk. Throughout the three days we were there I mostly remember missing out on cocktail parties while she napped, trailing behind her as she insisted on climbing up and down the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, and trying to subdue her as she cried and squirmed her way through each formal event.

I was a mess and I was resentful. I wanted to scream at each person who reminded me how brilliant Andy was. I imagined walking around the galleries sticking post-it notes under each piece of art listing the names and roles of all the people behind the scenes who sacrificed so that these artists could devote their lives to their work. Who did the laundry? Who paid the bills? Who made the doctors appointments and the dinners when these people were following their inspiration and spending all waking hours in their studios? Who picked up the slack? Who provided possible solutions to creative problems, advice when they were stuck or reassurance to keep going when they felt defeated by the harsh realities of trying to make a living as an artist in our capitalist hellscape?

I lost myself in those years. No matter how fulfilling I found my new role as a parent, I couldn’t shake the feeling that I’d severed a connection to a precious and essential piece of myself. I worried that I’d somehow traded away my rights to a creative life without realizing it was happening, and that it might be too late to change course.

It took years of tear-filled conversations, fights, negotiations and a complete re-organization of our roles in our marriage to resurrect my creative practice.

When Andy moved into a larger studio with our friend Droo, he set aside space at one of his work tables so that I could start printmaking again. For a few hours each weekend I escaped to the beautiful light-filled studio and began to experiment, excavating the pieces of myself that had been slowly buried.

Still, it wasn’t enough. When Cleo was five we moved into our current home and he helped me to convert a tiny upstairs room in our house into my first studio space. Finally having a room of my own—a place where I could wander in and find my things exactly where I’d left them, my projects spread out on my worktable and the floor; images, lists, and ephemera tacked to the walls and a window with a view of our dogwood tree—revived the parts of me that had withered.

To write about all of this as if it is something settled and relegated to my past is to gloss over the very real challenges of making this creative partnership work. There is still constant re-negotiation and recalibration, collaboration and compromise. There are periods when one person is productive, and the other is struggling. Sometimes I feel envy and resentment. The pull of structural inequity and tradition (ahem, patriarchy) relentlessly tests our fortitude and forces us to re-invent how we make our partnership work over and over again. So does the fact of money and how we make it.

What’s been most astonishing about this year is that both of us have been able to immerse ourselves in our respective creative worlds. We’ve been released from the tug-of-war of who gets to step away to create, and for how long. And perhaps that makes Venice my muse, or more specifically, my muse is the time and space that being here has afforded me. It’s what I’ll miss most when we leave.

That’s it for now, dear reader. Thanks for sticking it out with me. If you feel inclined, feel free to share.

xo, Belle

Hot Links:

Cleo and I are blasting through some of the best seasons of Survivor. So far we’ve watched David and Goliath (Mike White!) and Millennials vs. Gen X. We both scream, gasp and talk shit through each episode. Cleo is preparing to be the youngest contestant ever, and I am here for it. Cross your fingers that it’s still on air 6 years from now so she can win us a million dollars.

I finally read William Finnegan’s book Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life (it won the Pulitzer in 2016). In short: Surfing, travel, surfing, California history, Hawaii, surfing, and so many descriptions of waves. I both loved it and also found it moderately boring at times—kind of like listening to your husband describe a particularly epic surf session.

I just started my friend Quinn Slobodian’s newest book Crack up Capitalism. This review of it in the LA Review of Books is a great primer. Also, my bestie Ryan made a trailer for it (a book trailer!) that’s both stylish and harrowing.

I also am not ashamed to say that I spent hours of my life watching Ramit Sethi’s reality show How to be Rich (terrible show name, not a reflection of the tone of the show), which basically follows the super charismatic Ramit as he helps different people struggling to figure out how to pull themselves out of debt, manage their money, or work through their dysfunctional relationship with spending and saving. What ended up completely blowing my mind about the show—aside from the plentiful and gratuitous b-roll shots of his butt—was actually the bleak uniformity of the “modern” interior spaces that many of the people featured on the show inhabit. I have SO many thoughts about the tyranny of the Airbnb aesthetic (we’ve spent the year living in a grey-dominant Airbnb style apartment ) and there were some seriously egregious examples of the lifeless, antiseptic and soul-killing design that has taken over the world on the show. I’ve been joking lately that I want everything to look like the 15th century, but feel like some utopian vision of the future I dreamed up while reading Sassy magazine in 1993. Enough said.

And finally, our beloved friend Bruce Johnson passed away tragically a few weeks ago. He was not only a top-notch human in every regard, but also a prolific and massively talented artist. This documentary about his work is well worth a watch.

What a heartbreaking and heartwarming piece. All I can say is, you got this sis! You’ve got the chops, brain and brawn to do the things - any of them you choose. Love the art history and her-story. Keep it coming!

I am always struck by how thoughtful and well- crafted your essays are, describing so many issues, experiences, generations and emotions that we enjoy and learn from. I hope to meet you in person one day. Went to elementary school with your mom.