In 2006 the skeleton of an old woman was unearthed from a “plague pit” on the island of Lazzaretto Nuovo in the Venetian Lagoon. The discovery of this woman’s skull caused a stir in certain circles because of the brick lodged between her teeth; a signal to archaeologists that they had possibly uncovered the origins of the myth and ritualized exorcism of a vampire.

There is no way to know who this woman was, or anything about the life she led, other than the fact that she survived into her 70’s at a time when the average lifespan in the region was 30 to 40 years. We do know that she ended her time on this earth tossed unceremoniously into a pit, layered like “lasagna” alongside the bodies of thousands of her fellow Venetians.

I am a child of the American West. I was raised in the Santa Clara Valley —also known as the Valley of Heart’s Delight—fed on the promise of the limitless potential of technology and agriculture, nurtured by wide expanses and the promise of the new. I understand the roil of the Pacific ocean, oak savannas, freeways and strip malls. My closest proximity to mass death—that I could see—was driving north on 280 past the military cemetery in Colma on weekend trips to my grandparents’ apartment in San Francisco. The sight of all those tombstones sprouting like a sea of orderly white teeth made me recoil; I’d suck in my breath and avert my eyes each time we made the journey, afraid to even begin to think about what all those rectangles really meant.

But here— here death is omnipresent and the weight of history is thick and muggy.

On my first visit to Venice with Cleo and Andy in 2018, I was thrown off balance by something unnameable about the city that made my hair stand on end. The famed Italian light and sparkling water contrasted magnificently and eerily against the gothic darkness of the place. Everywhere I looked there seemed to be a finger of a saint entombed in a glass reliquary, a marble crypt that I was sidestepping across, or an imposing statue staring down menacingly from the centuries. This city, a marvel of human ingenuity, engineering, art and architecture, was also a living memorial to death.

I started digging online, trying to comprehend the origins of the morbid vibes in this “most romantic city on earth.” It took little time before I began unearthing the source of so much darkness: The Black Death. Each night at dinner I shared my findings with Andy and Cleo; stories of people bricking up the windows and doors of the houses of the infected while they were still alive inside, far flung conspiracies of poisoned wells and black magic, and of a city irrevocably altered by loss. Little did I know that just two years later, I’d be returning to those stories with the eyes of the newly initiated.

Once you start looking, evidence of the the plague that terrorized much of Europe and Asia over the course of hundreds of years is everywhere in Venice. You can see it in the replica plague doctor masks tacked to the walls of costume shops and in the magnificent basilicas erected to commemorate its multiple “endings”: Maria Salute and Il Redentore. There are still two major festivals celebrated throughout the year to honor the memory of the victims as well as the survivors, the Feast of Madonna Della Salute (plague of 1630) and the Feast of Redentore (the plague of 1575 and 1577), when Venetians eat, drink, detonate fireworks and collectively remember the plight of their ancestors.

It even turns out that my favorite sotoportego, one that I walk under multiple times a week and admire for its anomalous beauty, was constructed as an offering to protect the faithful against the terrors of the plague of 1630. Inscribed onto one of the walls is the quote: “Keep out, evil plague, and do not dare enter this courtyard, since it is blessed by Mary.”

This month marks the third anniversary of our own pandemic. I am writing to you across an ocean, a different version of the person I was on March 12, 2020. I have no coherent or tidy way of summing up the soupy morass of grief, frustration, anger, love, fear, idealism, exhaustion and overwhelming gratitude I feel when I think of the past three years.

So I’ve decided to look backwards as a way to make sense of it all. I want to understand how the survivors of the Black Death navigated the “after,” (though, there really was no such thing) and began to rebuild after so much devastation and loss. I believe that much of what they experienced is echoed in our current circumstances.

The first plague of the Black Death reached Venice in January of 1348. Over the course of the next nine months, an estimated third to one half of the city’s population was wiped out.

One of the most pressing issues Venetians had to contend with was how and where to bury the bodies, as the lack of soil in a floating city poses significant challenges when it comes to in-ground burial. Short of space and frantic to dispose of bodies they believed were emitting contagious vapors, city officials decided to transport and bury the bodies of the deceased in plague pits on distant islands in the Lagoon.

Afraid, terrorized and desperate, many of the survivors pointed fingers in any direction they could to explain how and why they’d been punished so brutally. The overwhelming scale of the misery—of mass death and devastation so swift and widespread—propelled them into answer-seeking that led to persecution and harmful mythologies and conspiracy theories that still persist.

Some found their scapegoats in the already marginalized, condemning the Romani, lepers, Turks and Muslims for spreading the disease. And, some, returning to perennially useful antisemitic tropes, blamed the Jews for poisoning wells with the pestilence, claiming an international conspiracy to destroy Christendom, and ultimately sowing the seeds for a wave of mass killings and expulsions of Jews across Germany, France and Austria during the plagues that followed.

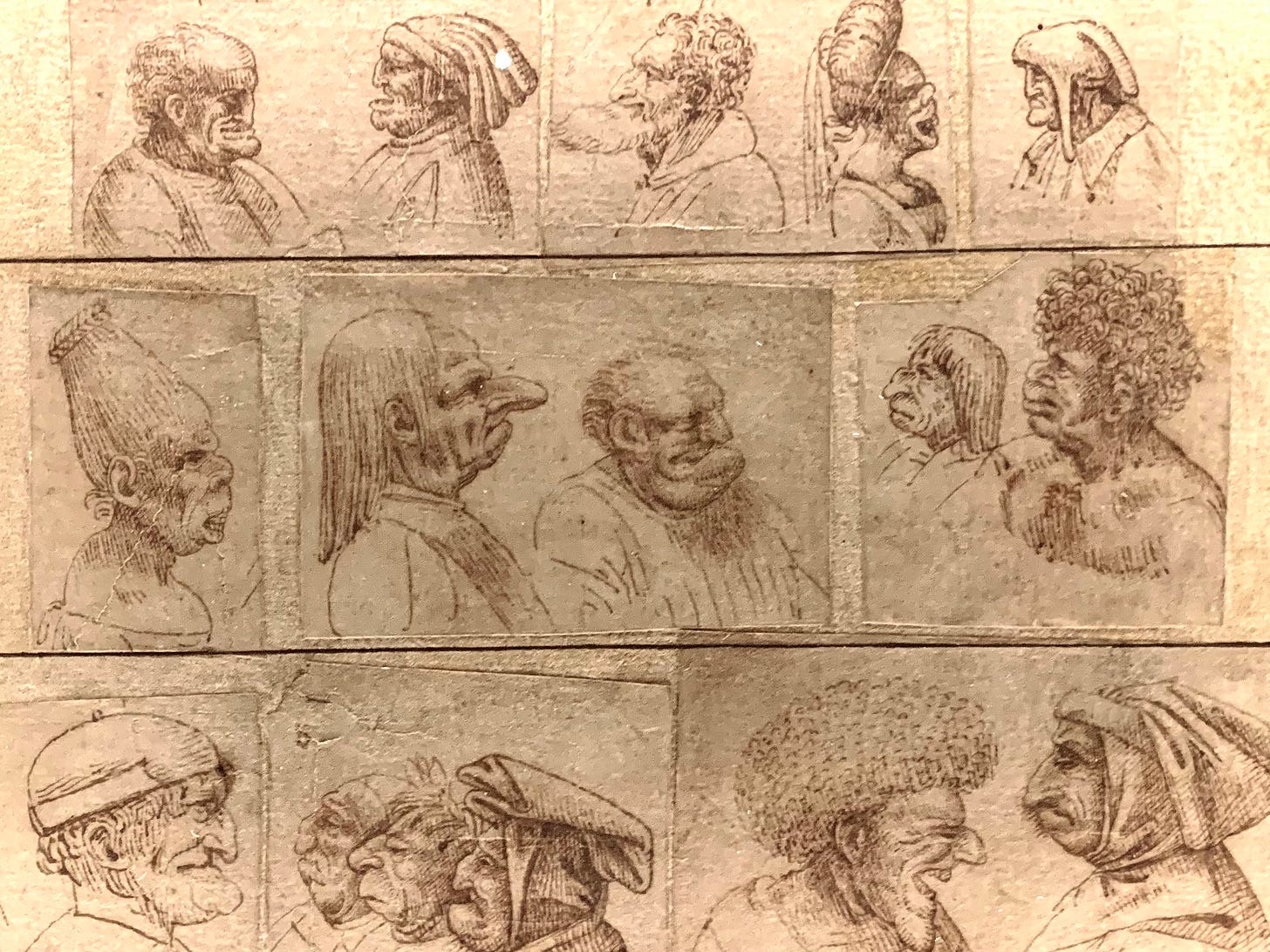

In subsequent outbreaks of the plague, still lacking answers and consigned to weathering each outbreak with few defenses and very little hope, the blame fell on supernatural forces of the devil: vampires and witches.

You see, during the middle ages there was little known about the way a body decomposes over time. Gravediggers, while burying bodies in mass graves, often encountered corpses that appeared to be bleeding from the mouth through their burial shrouds. They mistook the fluids released by the body after death for blood, believing the decomposing corpses to still be alive, and feeding off of other corpses until they could eventually return to the land of the living as “shroud eaters” — also known as vampires. In order to kill the vampire, the shroud was removed, and something inedible, like a brick, was put in its place.

And that’s how the old woman ended up in a plague pit with a brick lodged between her jaws.

After the first devastating wave of the plague, Venetian authorities focused on the need to protect the city from potential infection arriving via the sea. Over the course of the next outbreaks, a public health response was initiated by the Venetian Republic, designating the island of Lazzaretto Vecchio for isolating and treating plague-stricken Venetians and the island Lazzaretto Nuovo for sequestering ships entering the Lagoon.

After being detained on the island, the sailors would spend a period of 40 days—quaranta giorni— before being allowed to enter the city. This 40 day period is where we get the word “quarantine.” When we were sequestered in quarantine during those terrifying first few months of the pandemic, we were also communing with the Venetians who had the foresight— with extremely limited scientific understanding—to protect the city’s inhabitants through isolation and observation. And just for the record, they didn’t much like it either.

During one of the subsequent plagues of 1555-57, the death toll in Venice was so high that there was no time to move the bodies on boats—usually 40 bodies at a time—out to the established burial pits on the two islands. So, they dug up the stones in many of Venice’s squares, where they could access the deepest soil, and piled the bodies underneath.

Today, every time a city infrastructure project is undertaken, or as erosion resulting from climate change threatens the foundations of buildings, there is the possibility of accidentally exhuming victims of the Black Death— their bones still potentially containing live plague bacteria that can survive for hundreds of years in humid conditions.

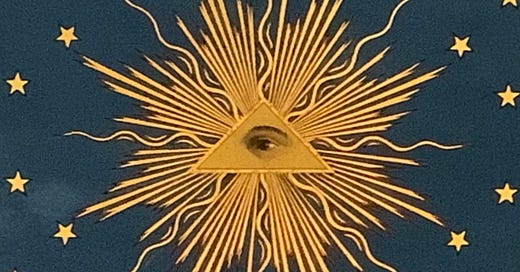

Responses to the devastation wrought by mass illness and death were as varied as the responses to our own pandemic. Some doubled down on their investment in the Church, turning towards deeper religiosity and the predictability of a system and structure of beliefs that they hoped might protect them from future horrors. Religious extremism flourished, with groups like the flagellants — who walked in procession dragging crosses, chanting and whipping themselves in penance for perceived sins—becoming increasingly popular. Same sex unions, believed by scholars to be tolerated and sometimes even celebrated during the middle ages, were outlawed after the plague by the Catholic Church, mainly because of the new focus on a need to repopulate.

And yet, overall, faith in organized religion decreased after the plague, both because of the death of so many of the clergy and because of the failure of prayer to prevent sickness and death. Most people were set adrift, newly disillusioned with Catholicism and untethered by the crumbling structures of a society altered by unimaginable grief and loss.

Some people channeled their fears of the plague by placing their faith in conspiracy theories for answers, despite the lack of any proof or validity of their beliefs. According to historian Helen Christian, “The plague represented one of the first instances where persecutors were confronting the idea of a secret evil conspiracy of which there would never be any actual evidence—the fabled instructional pamphlets on how to destroy Christendom and the vials labeled “poison for the wells” never materialized.” And yet, people continued to believe, promote and act upon these conspiracies.” Sound familiar?

Still, the need to imagine and build something new was urgent and unavoidable: people needed to eat. Women, who had enjoyed few rights in the feudal economy, were thrust into the workforce, their roles irrevocably changed by necessity — there simply weren’t enough men to do all the jobs that needed doing. The shortage of workers prompted waves of labor uprisings that ultimately resulted in raised wages for peasants and challenges to the structure of feudalism, as many of the workers abandoned feudal manors to look for new types of work in towns and cities. The rigid social hierarchy of the middle ages was ultimately upended, creating potential for a fluid re-organization of societal structures.

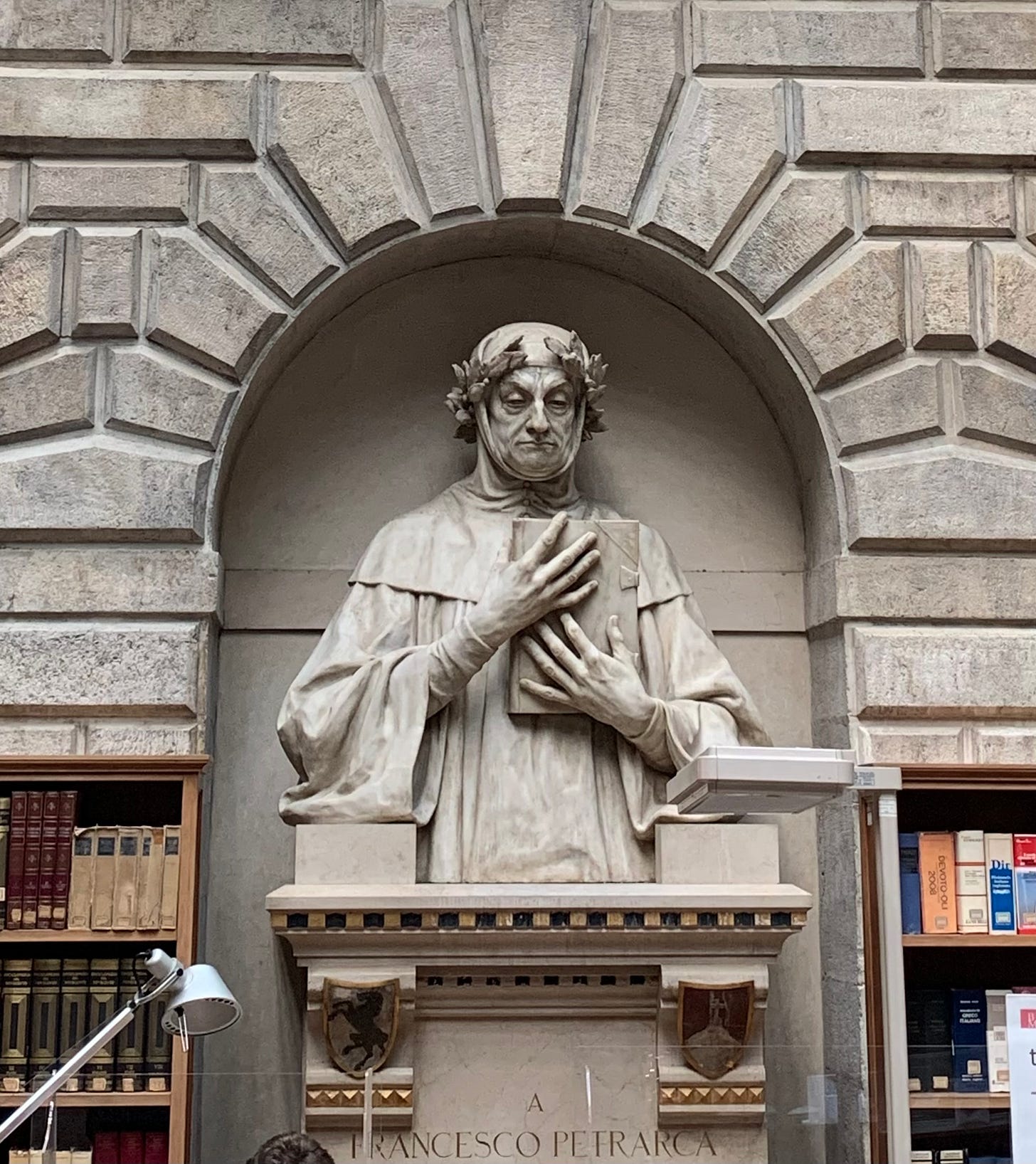

Unceasing confrontation with death led others to channel their grief into lifelong pursuits of meaning-making. As I was searching for first person accounts of the aftermath of the first plague, I stumbled upon a history of Francesco Petrarch (Petrarca), who coincidentally watches over me while I write in the library.

Petrarch was a poet, philosopher, mountain climber and inveterate wanderer. A few years before the plague of 1348, he discovered a long-forgotten stash of Roman orator Cicero’s letters in the library of a cathedral in Verona. His mind was blown by what he found: Cicero’s writing seemed to elucidate all the knowledge that had been lost from classical antiquity after the fall of Rome (a period Petrarch named the “Dark Ages”).

During the outbreak of the the first plague and those that followed, he traveled throughout Italy, sharing what he learned from Cicero in letters and poems as a kind of medieval hype man for ancient wisdom. His writings from this time are credited as the philosophical foundation of the intellectual, artistic and scientific pursuits of the Italian Renaissance, and the push towards “modernity” in Europe.

His letters also tell a story of a man consumed by grief, forced to reckon with the loss of almost everyone he loved during the successive outbreaks of the plague. “Where are our dear friends now? Where are the beloved faces? Where are the affectionate words, the relaxed and enjoyable conversations?.... We should make new friends – but how, when the human race is almost wiped out; and why, when it looks to me as if the end of the world is at hand?.... You see how our great band of friends has dwindled.” Despite losing everything, he remained steadfast in his determination to spread knowledge and beauty, and sow the seeds of what he imagined could be a better world.

This crazy thing, this fucking pandemic, it happened. When we push it all down without processing, grieving or even acknowledging, we dishonor those we lost. Not only the 6,811,729 people worldwide (as of today) who died from Covid 19, but the countless others like my aunt Marcia, who died from unexplainable heart failure after she contracted Covid, and my dear friend Judy who chose to to end her life during the first agonizing year of pandemic isolation.

Honoring the dead also means not losing sight of what was life-affirming about the pandemic. That being forced to slow down felt like a momentary reprieve from end-game capitalism. That it only took a few weeks of non-productivity for our earth to remind us that regeneration and healing is possible. And that ultimately we really do need one another and are only as strong as the communities we build.

Covid was a disruptor. It shook the foundation of our institutions, our beliefs, our communities and our families. It divided us in ways we couldn’t have predicted, and united some of us in ways that we should not take for granted. It also provided us with an opportunity to change course — and that’s the part I’m trying to hold on to.

I don’t want to forget. I don’t want to just move forward. I want to build monuments and memorials, I want to plant forests and gardens, write songs, cook feasts and remember. I want rituals and celebrations. I want to honor the dead, support the grieving and care for those afflicted with long Covid. And I want to do it communally, not alone.

Death is our one collective certainty. When we deny death, we lose the connection between those who came before, and those who will come after. So let’s not surrender the narrative to people in denial and anyone who seeks to minimize, distort or profit from forgetting. Let’s tell our stories.

As Pema Chodron says: “Things falling apart is a kind of testing and also a kind of healing. We think that the point is to pass the test or to overcome the problem, but the truth is that things don’t really get solved. They come together and they fall apart. Then they come together again and fall apart again. It’s just like that. The healing comes from letting there be room for all of this to happen: room for grief, for relief, for misery, for joy.”

Next time there will be unicorns and rainbows, I promise.

Oh, and while you’re here, do me a solid: If you feel like sharing my writing with a friend, I’d be humbled and super grateful.

Until next time,

xo, Belle

Hot Links:

This article by Leslie Jamison in the New Yorker about questioning the validity of “impostor syndrome” is a fascinating read.

"It’s Friends who will Break Your Heart” by Jennifer Senior in the Atlantic prompted some marathon phone conversations with my best friend. The piece is an insightful and thought-provoking look at how and why some friendships end and others are sustained throughout our lives.

I read and really liked Severance by Ling Ma. She wrote it in 2017, but it is weirdly prescient. It’s the story of a pandemic in which the infected die very slow deaths after breathing in spores of a fungus that makes them repeat their work routines until they finally just expire. Lots to think about in terms of late capitalism and relationships in this one. Be forewarned: the ending is incredibly abrupt and unsatisfying.

If you’re into plague lit like me (I realize this is demented) Year of Wonders by Geraldine Brooks is my favorite fictional account of the plague (based on the true story of the town of Eyam in 1666 England). Brooks is an incredible writer and this book leveled me when I read it during quarantine in 2020.

The three of us are blazing through the show Only Murders in the Building. It is consistently funny and Selena Gomez is a revelation! Also, whoever did the art direction (the wallpapers, holy shit) is a goddamn genius.

I just finished The Overstory by Richard Powers. I have a lot of conflicting feelings about this book. First off, I should say that I really wanted to love it. I learned SO much about trees (fascinating), and I was deeply invested in sections of the narrative —especially the beginning—but I couldn’t escape this nagging feeling that it was way too long. While I was reading it I also couldn’t stop thinking about Stephen King’s The Stand, as the structure and narrative progress similarly, and Powers writes about female beauty and flattens out female characters in the same cliche and predictable “but omg she’s gorgeous!” way that King does. Sigh. Anyway, I digress. I love trees! Trees are the best! Glad he’s getting the word out.

Written with deep feelings and inner visions, as always, Belle Violet. You must have researched a great deal for this piece. Plagues are not a happy topic. And Venice has more history of it than anyplace here in this country. Fascinating in a macabre sort of way.

Maggi had recommended the Geraldine Brooks book to me several years ago. I was kind of afraid to read it. Maybe I finally will.

So many lessons to be learned from our own pandemic that will take years to process.

After all these centuries, humans haven’t really changed very much when responding to the unknown.

Love you guys and miss you a great deal. ❤️

need to get into some plague lit!